Modelling domain with state machines in ReasonML

In this article we are going to focus on modelling state and state handling logic of a system in a functional way, without touching the user interface.

The idea behind “functional way” here is applying functional patterns and constructs in order to:

- model the domain area correctly making impossible states unrepresentable,

- handle domain logic eliminating impossible transitions on the state,

- create a convenient interface for manipulating state that can be plugged in into any frontend (but not necessarily) application,

- write readable and succinct code (less code - fewer bugs 🐛).

The code examples are written in ReasonML, but will look very similar in other functional languages such as F# or Elm. Some familiarity with functional concepts in general will help along the way, but not required.

Important concepts that we will use extensively:

- Immutability and pure functions,

- Variants and pattern matching,

- Partial application and currying.

Just wanted to emphasise that we won’t mutate anything here, since it might lead to unexpected bugs, systems that are difficult to follow and debug, and unexpected bugs. Did I mention unexpected bugs?

Overview

Let’s imagine that we are building a time tracking system, like an upgraded to-do list, where the user can keep track of how much time it takes to finish tasks. Such a system can be used as a personal tool in private projects or a time reporting tool for software developers at work.

We will create a module for handling state of this system, gradually introducing more concepts along the way. Our best functional friends in this article will be variants (or discriminated union in F# and custom types in Elm) and pattern matching, which we will use to build a state machine.

The source code is available on github.

Modelling task

According to the requirements of the system, we should be able to:

- add tasks,

- start added and pause running tasks,

- mark running or paused tasks as done,

- keep track of how much time a task has been run.

So apart from having a name and probably id, a task should know whether it is running, paused, done etc., which we will call status. Then our task could look like this:

type task = {

id: string,

name: string,

status: ???,

}The status can only be assigned one of the following values:

- not started (just added),

- running with how much time it has been running,

- paused with how much time it ran before it was paused,

- finished with how much time it took in total.

Moreover, there are special rules that define whether a task can change its status to a particular value. For example, it wouldn’t make sense to pause a task that is done, or start an already running tasks, however it is perfectly fine to set paused or running tasks as done. And the best way to model these rules is using a state machine, which is…

State machine

A mathematical model defined by a certain (limited!) number of states, where it can only be in one of these states at a time and can transition between the states based on the current state and some input.

My first reaction to the definition of a state machine was similar to the one of a “monad” 😨 But let’s not allow it happen to you, reader! Simply put, it is a thing that has a limited number of predefined values, the thing can’t change its value arbitrary, in order to choose the next value it needs to know the current value and some external input (like a user action).

State transitions in a state machine can be represented as a function:

nextState=transition (currentState, input)

We will model our status property as a state machine and represent its possible states with a ReasonML variant:

type elapsed = float;

type taskStatus =

| NotStarted

| Running(elapsed)

| Paused(elapsed)

| Done(elapsed);Each state except NotStarted, will hold a time interval which we will represent as float with an alias elapsed (just for clarity). Those are the possible states of our little state machine. Now, we can define valid state transitions as a following table:

- NotStarted -> Running

- Running -> Paused

- Running -> Done

- Paused -> Running

- Paused -> Done

I will add one more transition from Running to Running with elapsed time increased after each timer tick. The input that the state machine will accept can be represented as a variant too:

type input =

| Start

| Pause

| Resume

| Finish

| Tick(elapsed);Here Tick with elapsed time will come from a timer running somewhere in the app, while all the other input values will trigger state transition from the user input (e.g. click on the “Pause” button in the UI).

Before we implement our transition function, let’s look into how we can visualise our state machine with an online tool.

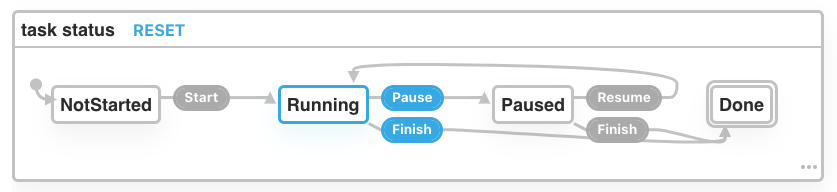

State machine visualiser

A great way to illustrate the states and transitions of a state machine is to visualise them with a state diagram. There is an open source visualiser as part of the xstate library, which is an interactive tool where you can click on state transitions and see how state changes.

Check the task-status example live here, and here is a little preview:

Transition function

The transition function itself will accept a value of type input and the current state, and do a pattern match on both values matching only on valid combinations of pairs (state, input):

let transition = (input, state) =>

switch (state, input) {

| (NotStarted, Start) => Running(0.0)

| (Running(elapsed), Pause) => Paused(elapsed)

| (Running(elapsed), Finish) => Done(elapsed)

| (Paused(elapsed), Resume) => Running(elapsed)

| (Paused(elapsed), Finish) => Done(elapsed)

| (Running(elapsed), Tick(tick)) => Running(elapsed +. tick)

| _ => state

};The last case will handle all invalid transitions by returning the current state.

EDIT: I have been pointed out that when handling default cases with a wildcard match (_), it is easy to miss potentially valid transitions. Moreover, when making changes and adding states or inputs, the compiler won’t give any warning if not handling all combinations explicitly. And I agree!😅

However, in more complex systems with many states and inputs, it becomes unreasonable to account for all combinations, since the number of cases is state * inputs. But let’s see how we can do it for our little state machine:

let transition = (input, state) =>

switch (state) {

| NotStarted =>

switch (input) {

| Start => Running(0.0)

| Pause | Finish | Tick(_) | Resume => state

}

| Running(elapsed) =>

switch (input) {

| Pause => Paused(elapsed)

| Finish => Done(elapsed)

| Tick(tick) => Running(elapsed +. tick)

| Start | Resume => state

}

| Paused(elapsed) =>

switch (input) {

| Resume => Running(elapsed)

| Finish => Done(elapsed)

| Tick(_) | Start | Pause => state

}

| Done(_) => state

};A little bit more verbose, but still manageable.

Notice how we encode the business rules of the system in the transition function by allowing to move both running and paused tasks to done. If those rules have to change in the future (and they certainly will), there is only one place where we have to make adjustment and it is quite easy to modify the necessary transitions.

Speaking of making changes to the system and making sure nothing breaks, it is probably time to test our state machine and fortunately it is quite easy to do.

Testing

We will use bs-jest for writing tests in ReasonML and specifically the testAll function to generate tests based on lists of data.

Since we probably don’t want to write a test per each valid and invalid transition (that would make for a total of 20 tests), we will use testAll for just two tests - valid and invalid state transitions - to achieve 100% coverage.

Testing valid transitions:

testAll(

"Transition works correctly for valid state transitions",

[

(NotStarted, Start, Running(0.0)),

(Running(10.0), Pause, Paused(10.0)),

(Running(10.0), Finish, Done(10.0)),

(Paused(10.0), Resume, Running(10.0)),

(Paused(10.0), Finish, Done(10.0)),

(Running(10.0), Tick(15.0), Running(25.0)),

],

((currentState, input, nextState)) =>

expect(currentState |> transition(input)) |> toEqual(nextState)

);Here we are feeding a tuple of three values into each test: currentState, input and the expected next state.

Testing invalid transitions is very similar. We will pass a tuple of a list of states and an input, where each of the combination (state, input) is invalid and should result in the same state after applying the transition function.

testAll(

"Transition returns current state for invalid state transitions",

[

([|Running(10.0), Paused(10.0), Done(10.0)|], Start),

([|NotStarted, Paused(10.0), Done(10.0)|], Pause),

([|NotStarted, Running(10.0), Done(10.0)|], Resume),

([|NotStarted, Done(10.0)|], Finish),

([|NotStarted, Paused(10.0), Done(10.0)|], Tick(15.0)),

],

((states, input)) =>

expect(states->Belt.Array.map(state => state |> transition(input)))

|> toEqual(states)

);Summary

State machines help model domain area correctly making sure invalid states and transitions are simply impossible. Moreover, with tools like xstate visualiser we can discover hidden states or edge cases in a complex system by visualising it with a state diagram.

State machines are especially useful in frontend development, since a rich app will typically have a fair amount of state that changes based on the user actions. Since the user will probably not use your app as you would expect, eliminating invalid state transitions when the user clicks on the wrong button will spare your app a few crashes 💥

And the truth is, once you understand a state machine, you will see it everywhere (you are welcome!). However a language that supports variants (or discriminated unions) will truly uncover the power and beauty of state machines.

What’s next

In the next article I will show how to manipulate a list of tasks in order to implement extra business requirements while writing nice, compact and readable code using partial application and reducer pattern. Coming 🔜